Articles

Hitler did not fear

retribution for the Holocaust. Why? He

didn’t think the world would care, asking as

he prepared to invade Poland “Who today

still speaks of the massacre of the

Armenians?”In 1915, there were 2 million

Armenians living in the declining Ottoman

Empire. But under the cover of World War I,

the Turkish government systematically

destroyed 1.5 million people in attempts to

unify all of the Turkish people by creating

a new empire with one language and one

religion.

Hitler did not fear

retribution for the Holocaust. Why? He

didn’t think the world would care, asking as

he prepared to invade Poland “Who today

still speaks of the massacre of the

Armenians?”In 1915, there were 2 million

Armenians living in the declining Ottoman

Empire. But under the cover of World War I,

the Turkish government systematically

destroyed 1.5 million people in attempts to

unify all of the Turkish people by creating

a new empire with one language and one

religion.

This ethnic cleaning of Armenians, and other

minorities, including Assyrians, Pontian and

Anatolian Greeks, is today known as the

Armenian Genocide.

Despite pressure from Armenians and

activists worldwide, Turkey still refuses to

acknowledge the genocide, claiming that

there was no premeditation on the deaths of

the Armenians.

Despite pressure from Armenians and

activists worldwide, Turkey still refuses to

acknowledge the genocide, claiming that

there was no premeditation on the deaths of

the Armenians.

Precursors to Genocide

History of the Region

The Armenians have lived in the southern

Caucasus since the 7th century BC and have

fought to maintain control against other

groups such as the Mongolian, Russian,

Turkish, and Persian empires. In the 4th

century, the reigning king of Armenia became

a Christian. He mandated that the official

religion of the empire be Christianity,

although in the 7th century AD all countries

surrounding Armenia were Muslim. Armenians

continued to be practicing Christians,

despite the fact that they were many times

conquered and forced to live under harsh

rule.

The roots of the genocide lie in the

collapse of the Ottoman Empire. At the turn

of the 20th Century, the once widespread

Ottoman Empire was crumbling at the edges.

The Ottoman Empire lost all of its territory

in Europe during the Balkan Wars of

1912-1913, creating instability among

nationalist ethnic groups.

The First Massacres

There was growing tension between Armenians

and Turkish authorities at the turn of the

century. Sultan Abdel Hamid II, known as the

“bloody sultan”, told a reporter in 1890, “I

will give them a box on the ear that will

make them relinquish their revolutionary

ambitions.”

In 1894, the “box on the ear” massacre was

first of the Armenian massacres. Ottoman

forces, military and civilians alike

attacked Armenian villages in Eastern

Anatolia, killing 8,000 Armenians, including

children. One year later, 2,500 Armenian

women were burned to death in Urfa

Cathedral. Around the same time, a group of

5,000 were killed after demonstrations

begging for international intervention to

prevent massacres upset officials in

Constantinople. By 1896, historians estimate

that over 80,000 Armenians had been killed.

The Rise of the Young Turks

In 1909, the Ottoman Sultan was overthrown

by a new political group – the “Young

Turks”, a group eager for a modern,

westernized style of government. At first,

Armenians were hopeful that they would have

a place in the new state, but they soon

realized that the new government was

xenophobic and exclusionary to the

multi-ethnic Turkish society. To consolidate

Turkish rule in the remaining territories of

the Ottoman Empire, the Young Turks devised

a secret program to exterminate the Armenian

population.

WWI

In 1914, the Turks entered World War I on

the side of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian

Empire. The outbreak of war would provide

the perfect opportunity to solve the

“Armenian question” once and for all.

Military leaders accused Armenians of

supporting the Allies under the assumption

that the people were naturally sympathetic

toward Christian Russia. Consequently, Turks

disarmed the entire Armenian population.

Turkish suspicion of the Armenian people led

the government to push for the “removal” of

the Armenians from the war zones along the

Eastern Front.

Genocide Begins

Transmitted in coded telegrams, the mandate

to annihilate Armenians came directly from

the Young Turks. Armed roundups began on the

evening of April 24, 1915, as 300 Armenian

intellectuals – political leaders,

educators, writers, and religious leaders in

Constantinople – were forcibly taken from

their homes, tortured, then hanged or shot.

The death marches killed roughly 1.5 million

Armenians, covered hundreds of miles and

lasted multiple months. Indirect routes

through wilderness areas were deliberately

chosen in order to prolong marches and keep

the caravans away from Turkish villages.

In the wake of the disappearance of the

Armenian population, Muslim Turks quickly

assumed ownership of everything left behind.

The Turks demolished any remnants of

Armenian cultural heritage including

masterpieces of ancient architecture, old

libraries and archives. The Turks leveled

entire cities including the once thriving

Kharpert, Van and the ancient capital at

Ani, to remove all traces of the three

thousand year old civilization.

No Allied power came to the aid of the

Armenian Republic and it collapsed. The only

tiny portion of historic Armenia to survive

was the easternmost area because it became

part of the Soviet Union. The University of

Minnesota’s Center for Holocaust and

Genocide Studies compiled figures by

province and district that show there were

2,133,190 Armenians in the empire in 1914

and only about 387,800 by 1922.

An Unsuccessful Call to Arms in the West

At the time, international informants and

national diplomats recognized the atrocities

being committed as an atrocity against

humanity.

Leslie Davis, U.S. consul in Harput noted,

“these women and children were driven over

the desert in midsummer and robbed and

pillaged of whatever they had … after which

all who had not perished in the meantime

were massacred just outside the city.”

In a 1915 letter home, Swedish Ambassador

Per Gustaf August Cosswa Anckarsvärd noted,

“The persecutions of the Armenians have

reached hair-raising proportions and all

points to the fact that the Young Turks want

to seize the opportunity … [to] put an end

to the Armenian question. The means for this

are quite simple and consist of the

extermination of the Armenian nation.”

Even Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. Ambassador

to Armenia, noted “When the Turkish

authorities gave the orders for these

deportations, they were merely giving the

death warrant to a whole race.”

Even Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. Ambassador

to Armenia, noted “When the Turkish

authorities gave the orders for these

deportations, they were merely giving the

death warrant to a whole race.”

The New York Times also covered the issue

extensively — 145 articles in 1915 alone —

with headlines like “Appeal to Turkey to

Stop Massacres.” The newspaper described the

actions against the Armenians as

“systematic,” “authorized,” and “organized

by the government.”

The Allied Powers (Great Britain, France,

and Russia) responded to news of the

massacres by issuing a warning to Turkey,

“the Allied governments announce publicly

that they will hold all the members of the

Ottoman Government, as well as such of their

agents as are implicated, personally

responsible for such matters.” The warning

had no effect.

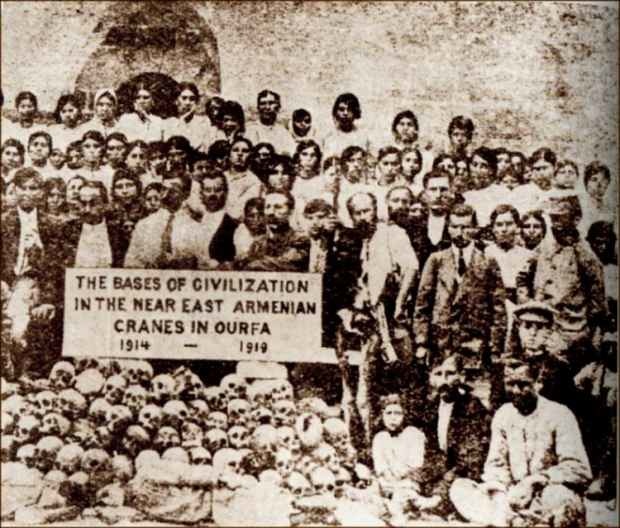

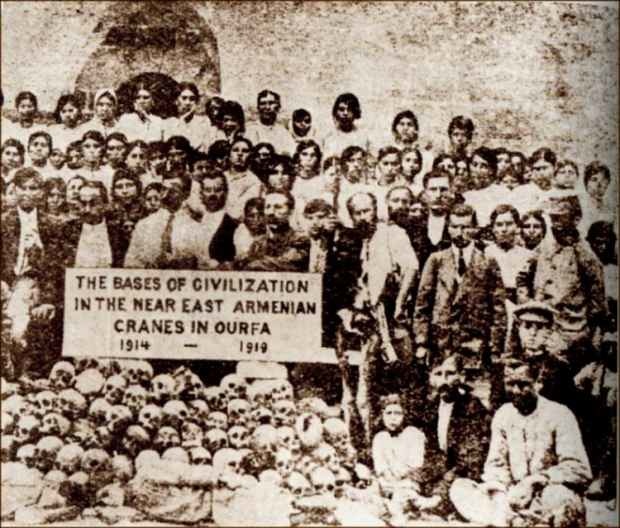

Because Ottoman Law prohibited taking

pictures of Armenian deportees, photo

evidence that documented the severity of the

ethnic cleansing is rare. In an act of

defiance, officers from the German Military

Mission documented atrocities occurring in

concentration camps. While many pictures

were intercepted by Ottoman intelligence,

lost in Germany during WWII, or forgotten in

dusty drawers, the Armenian Genocide Museum

of America has captured some of these photos

in an online exhibit.

Recognizing Genocide

Recognizing Genocide

Today Armenians commemorate those who lost

their lives during the genocide on April 24,

the day in 1915 when several hundred

Armenian intellectuals and professionals

were arrested and executed as the start of

the genocide.

In 1985, the United States named this day

“National Day of Remembrance of Man’s

Inhumanity to Man”, in “honor of all of the

victims of genocide, especially the one and

one-half million people of Armenian ancestry

who were the victims of the genocide

perpetrated in Turkey.”

Today, recognizing the Armenian Genocide is

a hot-button issue as Turkey criticizes

scholars for both inflating the death toll

and for blaming Turks for deaths that the

government says occurred because of

starvation and the cruelty of war. In fact,

speaking about the Armenian genocide in

Turkey is punishable by law. As of 2014, 21

countries total have publicly or legally

recognized this ethnic cleansing in Armenia

as genocide.

In 2014, on the eve of the 99th anniversary

of the genocide, Turkish Prime Minister,

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, offered condolences to

the Armenian people, saying, “The incidents

of the first world war are our shared pain.”

However, many feel that offerings are

useless until Turkey recognizes the loss of

1.5 million people as genocide. In response

Erdogan’s offering, Armenian President Serzh

Sarkisian said, “The denial of a crime

constitutes the direct continuation of that

very crime. Only recognition and

condemnation can prevent the repetition of

such crimes in the future.”

Ultimately, the recognition of this genocide

is not only important to redress the

affected ethnic groups, it is essential for

the development of Turkey as a democratic

state. If the past is denied, genocide is

still occurring. A Swedish Parliament

Resolution asserted in 2010 that, “the

denial of genocide is widely recognized as

the final stage of genocide, enshrining

impunity for the perpetrators of genocide,

and demonstrably paving the way for future

genocides.”

Hitler did not fear

retribution for the Holocaust. Why? He

didn’t think the world would care, asking as

he prepared to invade Poland “Who today

still speaks of the massacre of the

Armenians?”In 1915, there were 2 million

Armenians living in the declining Ottoman

Empire. But under the cover of World War I,

the Turkish government systematically

destroyed 1.5 million people in attempts to

unify all of the Turkish people by creating

a new empire with one language and one

religion.

Hitler did not fear

retribution for the Holocaust. Why? He

didn’t think the world would care, asking as

he prepared to invade Poland “Who today

still speaks of the massacre of the

Armenians?”In 1915, there were 2 million

Armenians living in the declining Ottoman

Empire. But under the cover of World War I,

the Turkish government systematically

destroyed 1.5 million people in attempts to

unify all of the Turkish people by creating

a new empire with one language and one

religion.This ethnic cleaning of Armenians, and other minorities, including Assyrians, Pontian and Anatolian Greeks, is today known as the Armenian Genocide.

Despite pressure from Armenians and

activists worldwide, Turkey still refuses to

acknowledge the genocide, claiming that

there was no premeditation on the deaths of

the Armenians.

Despite pressure from Armenians and

activists worldwide, Turkey still refuses to

acknowledge the genocide, claiming that

there was no premeditation on the deaths of

the Armenians.History of the Region

The roots of the genocide lie in the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. At the turn of the 20th Century, the once widespread Ottoman Empire was crumbling at the edges. The Ottoman Empire lost all of its territory in Europe during the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, creating instability among nationalist ethnic groups.

There was growing tension between Armenians and Turkish authorities at the turn of the century. Sultan Abdel Hamid II, known as the “bloody sultan”, told a reporter in 1890, “I will give them a box on the ear that will make them relinquish their revolutionary ambitions.”

In 1894, the “box on the ear” massacre was first of the Armenian massacres. Ottoman forces, military and civilians alike attacked Armenian villages in Eastern Anatolia, killing 8,000 Armenians, including children. One year later, 2,500 Armenian women were burned to death in Urfa Cathedral. Around the same time, a group of 5,000 were killed after demonstrations begging for international intervention to prevent massacres upset officials in Constantinople. By 1896, historians estimate that over 80,000 Armenians had been killed.

In 1909, the Ottoman Sultan was overthrown by a new political group – the “Young Turks”, a group eager for a modern, westernized style of government. At first, Armenians were hopeful that they would have a place in the new state, but they soon realized that the new government was xenophobic and exclusionary to the multi-ethnic Turkish society. To consolidate Turkish rule in the remaining territories of the Ottoman Empire, the Young Turks devised a secret program to exterminate the Armenian population.

In 1914, the Turks entered World War I on the side of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The outbreak of war would provide the perfect opportunity to solve the “Armenian question” once and for all.

Military leaders accused Armenians of supporting the Allies under the assumption that the people were naturally sympathetic toward Christian Russia. Consequently, Turks disarmed the entire Armenian population. Turkish suspicion of the Armenian people led the government to push for the “removal” of the Armenians from the war zones along the Eastern Front.

Transmitted in coded telegrams, the mandate to annihilate Armenians came directly from the Young Turks. Armed roundups began on the evening of April 24, 1915, as 300 Armenian intellectuals – political leaders, educators, writers, and religious leaders in Constantinople – were forcibly taken from their homes, tortured, then hanged or shot.

The death marches killed roughly 1.5 million Armenians, covered hundreds of miles and lasted multiple months. Indirect routes through wilderness areas were deliberately chosen in order to prolong marches and keep the caravans away from Turkish villages.

In the wake of the disappearance of the Armenian population, Muslim Turks quickly assumed ownership of everything left behind. The Turks demolished any remnants of Armenian cultural heritage including masterpieces of ancient architecture, old libraries and archives. The Turks leveled entire cities including the once thriving Kharpert, Van and the ancient capital at Ani, to remove all traces of the three thousand year old civilization.

No Allied power came to the aid of the Armenian Republic and it collapsed. The only tiny portion of historic Armenia to survive was the easternmost area because it became part of the Soviet Union. The University of Minnesota’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies compiled figures by province and district that show there were 2,133,190 Armenians in the empire in 1914 and only about 387,800 by 1922.

At the time, international informants and national diplomats recognized the atrocities being committed as an atrocity against humanity.

Leslie Davis, U.S. consul in Harput noted, “these women and children were driven over the desert in midsummer and robbed and pillaged of whatever they had … after which all who had not perished in the meantime were massacred just outside the city.”

In a 1915 letter home, Swedish Ambassador Per Gustaf August Cosswa Anckarsvärd noted, “The persecutions of the Armenians have reached hair-raising proportions and all points to the fact that the Young Turks want to seize the opportunity … [to] put an end to the Armenian question. The means for this are quite simple and consist of the extermination of the Armenian nation.”

Even Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. Ambassador

to Armenia, noted “When the Turkish

authorities gave the orders for these

deportations, they were merely giving the

death warrant to a whole race.”

Even Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. Ambassador

to Armenia, noted “When the Turkish

authorities gave the orders for these

deportations, they were merely giving the

death warrant to a whole race.”The New York Times also covered the issue extensively — 145 articles in 1915 alone — with headlines like “Appeal to Turkey to Stop Massacres.” The newspaper described the actions against the Armenians as “systematic,” “authorized,” and “organized by the government.”

The Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, and Russia) responded to news of the massacres by issuing a warning to Turkey, “the Allied governments announce publicly that they will hold all the members of the Ottoman Government, as well as such of their agents as are implicated, personally responsible for such matters.” The warning had no effect.

Because Ottoman Law prohibited taking pictures of Armenian deportees, photo evidence that documented the severity of the ethnic cleansing is rare. In an act of defiance, officers from the German Military Mission documented atrocities occurring in concentration camps. While many pictures were intercepted by Ottoman intelligence, lost in Germany during WWII, or forgotten in dusty drawers, the Armenian Genocide Museum of America has captured some of these photos in an online exhibit.

Today Armenians commemorate those who lost their lives during the genocide on April 24, the day in 1915 when several hundred Armenian intellectuals and professionals were arrested and executed as the start of the genocide.

In 1985, the United States named this day “National Day of Remembrance of Man’s Inhumanity to Man”, in “honor of all of the victims of genocide, especially the one and one-half million people of Armenian ancestry who were the victims of the genocide perpetrated in Turkey.”

Today, recognizing the Armenian Genocide is a hot-button issue as Turkey criticizes scholars for both inflating the death toll and for blaming Turks for deaths that the government says occurred because of starvation and the cruelty of war. In fact, speaking about the Armenian genocide in Turkey is punishable by law. As of 2014, 21 countries total have publicly or legally recognized this ethnic cleansing in Armenia as genocide.

In 2014, on the eve of the 99th anniversary of the genocide, Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, offered condolences to the Armenian people, saying, “The incidents of the first world war are our shared pain.”

However, many feel that offerings are useless until Turkey recognizes the loss of 1.5 million people as genocide. In response Erdogan’s offering, Armenian President Serzh Sarkisian said, “The denial of a crime constitutes the direct continuation of that very crime. Only recognition and condemnation can prevent the repetition of such crimes in the future.”

Ultimately, the recognition of this genocide is not only important to redress the affected ethnic groups, it is essential for the development of Turkey as a democratic state. If the past is denied, genocide is still occurring. A Swedish Parliament Resolution asserted in 2010 that, “the denial of genocide is widely recognized as the final stage of genocide, enshrining impunity for the perpetrators of genocide, and demonstrably paving the way for future genocides.”